ARTICLE – Your family has decided to move to a very rural locale, deep in the Rocky Mountains. You work from home full time, so reliable Internet connectivity is a must. Traditional satellite service is barely workable. What can you do?

Until a few years ago, the answer was simply, “don’t move.” Today, thanks to Elon Musk’s work to advance aerospace engineering, deploying hundreds of satellites is becoming a trivial, regular part of our modern existence. This capability has bred an entirely new network, with entirely new capabilities. But before we talk about Starlink, let’s look at what life was like before Starlink.

The (not so) good ol’ days of geostationary satellite

While “the Internet is a series of tubes” turned into a silly meme, it’s not an entirely false illustration. The whole Internet is connected – no matter where you are, if you’re online, your network traffic traverses the planet. So how do you connect to that network when you’re nowhere near modern infrastructure? The answer is RF, because RF allows for wireless communications, bridging the wired network – the tubes – with endpoints that might be anywhere on Earth, even the middle of the ocean. Depending on where you live, one popular RF option is microwave, which is high-frequency, high-speed, and relatively inexpensive…if you live somewhere suitable. In the Rockies, there are areas where the terrain makes microwave internet easily possible, but where we live, our small town is closely surrounded on all sides by mountains. This means that the only high-speed RF available is satellite Internet.

It used to be very expensive to deploy satellites, so satellite Internet providers, like HughesNet and ViaSat, rely on a very limited number of geostationary satellites, meaning satellites that match Earth’s rotation, so they are always in the same place relative to the planet’s surface. (You can read more about this technology here.) Because these satellites must provide a signal to entire segments of the North American continent, they’re positioned in a higher orbit, putting them further from the surface. This introduces a big problem for modern technology: latency. Traditional geostationary satellites are so far away from the receiving dish that latency can exceed a full second, making realtime communications (like VOIP and video chat) pretty much impossible. It also makes fun things, like online gaming, impossible, but more importantly, it makes full-time telework pretty miserable. The latency problem interferes with VPNs, remote desktop and virtual desktop services like Citrix and Windows 365, and causes constant headaches and problems with missed communication (and miscommunication!).

The low-orbit revolution

As many commentators and tech pundits have already discussed at length, Starlink revolutionizes satellite Internet, which means it revolutionizes global Internet access. For the first time ever in human history, true realtime, global, point-to-point communication is possible. There have long been satellite phone networks providing emergency phone service to the remotest locations on Earth, but they’re expensive and still suffer the same latency problems found with traditional satellite Internet services. Starlink is able to largely mitigate the latency problem – to the degree that voice and video calls are realistically possible – by building a global mesh of low-orbit satellites, rather than relying on a handful of geostationary satellites at higher orbit. As these satellites fly across the sky, a highly complex, intelligent dish tracks them, seamlessly maintaining connectivity.

This amazing technology is possible today because of many cumulative advancements in hardware miniaturization – that is, making tiny components that can do things we used to only be able to do with much larger components. While (comparatively) cheap spaceflight makes it economically feasible to deploy many satellites in building out a global mesh, the dish technology is the other part of the equation, and Starlink’s dishes are fancy. They include servos and logic processors and all kinds of fancy components that make the whole thing work as well as it does.

Starlink’s ability to conquer the latency inherent to geostationary communications satellites is truly revolutionary. It obliterates the competition in terms of performance, when the “the competition” refers to other satellite Internet providers. HughesNet is cognizant of this reality, and in December 2022 announced the acquisition of a low-orbit satellite communications company. This is great news for those of us living in geographies where satellite Internet is the only high-speed Internet service available, so it will be interesting to see how well HughesNet competes over time.

The cost of the future

Because the Starlink satellite dish is far more technologically complex than a typical home dish, the hardware is expensive – very expensive. As of this article, the standard hardware costs $599 (USD), and the performance hardware, which has a larger field-of-view, a much larger antenna array, and better extreme weather resistance, will set you back $2500. At this price, however, you own the hardware outright, so if you eventually decide Starlink isn’t for you, you can resell your old hardware on the used market – Starlink makes it easy to transfer ownership of hardware between accounts.

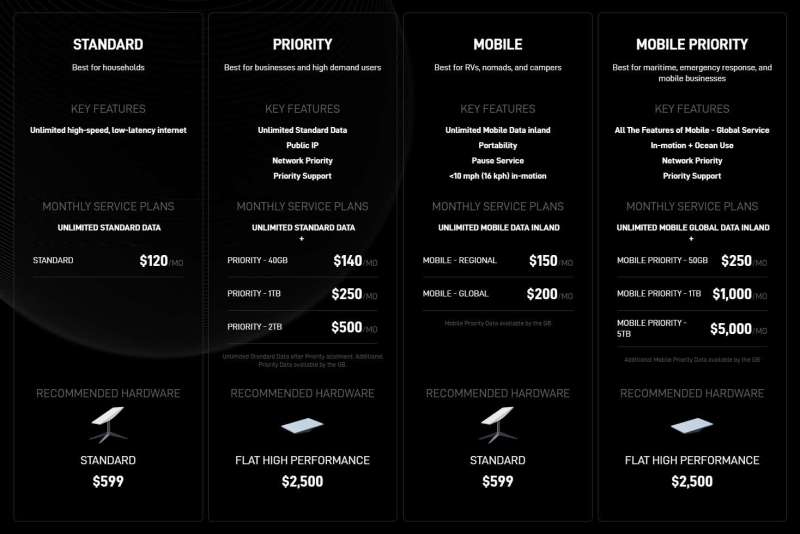

Service currently starts at $120 per month, and all tiers of service include unlimited standard data. If you are a business or otherwise have critical dependencies on Internet connectivity, you can upgrade to a priority plan, which gives you priority network access up to a limit, after which you can buy additional priority bandwidth, which currently runs fifty cents per gigabyte. Depending on your data consumption, priority service costs up to $500 per month. We currently have the $250/mo. mid-tier package, which includes a terabyte of priority network access. We decided to upgrade about a month ago, mostly because Starlink’s large expansion in user base has resulted in slower connectivity during peak times, and our remote work requirements necessitated the added expense for the added reliability.

You can get current details on Starlink’s service plans here.

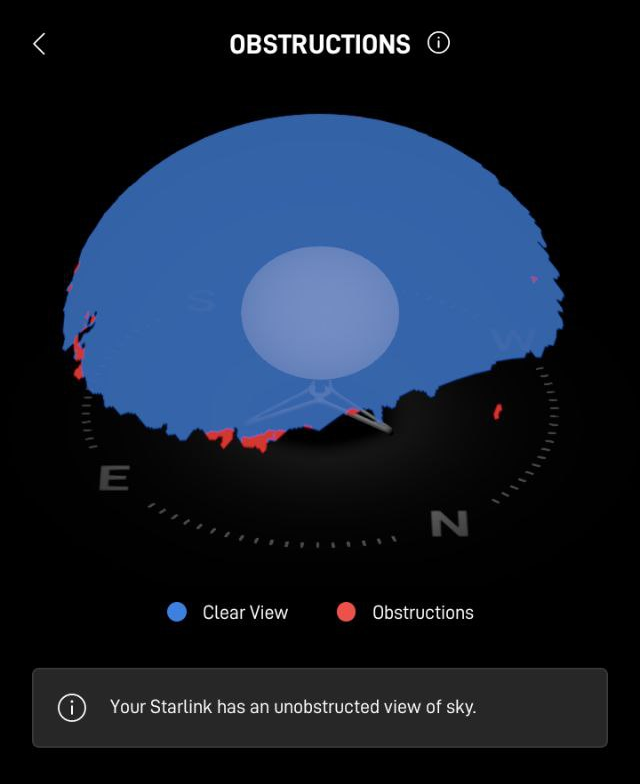

For the average household with no critical connectivity requirements, Starlink’s standard service works beautifully well. Uptime depends on dish visibility more than heavy traffic, and where we live there are still obstructions around the edge of our dish’s field-of-view, due to the steep mountains surrounding our property. On our to-do list is to install a much taller, telescoping pole on our property, so we can position the dish much higher in the air to clear the mountains.

If you have to deal with potential obstructions on your property, the Starlink app makes it easy to see where the obstructions are within the dome of your dish’s field-of-view.

Real-world performance

Satellite Internet is still more susceptible to interruptions than terrestrial, wired networks, and it can be slower during peak hours, because you’re sharing bandwidth with a very large geographical region compared to standard residential options, like cable and fiber. Network congestion is a real problem with Starlink, but it’s not a serious problem in terms of network reliability and usability. We’ve had Starlink for several years, and over the last 18 months, the company has added a lot of new subscribers, so network congestion has become more noticeable. This hasn’t interfered with any of our personal Internet usage – we can still easily stream in HD from Amazon and YouTube without excessive buffering (a second or two at most), and BitTorrent works just fine.

We upgraded to the (significantly) more expensive priority service to facilitate working from home. Employers care more than they did a few years ago about their work-from-home workforce, and there is pressure on many remote employees, with employers looking for opportunities to reduce remote workforces. If this fits your home Internet scenario, the priority service is definitely worth the extra money, and a terabyte of bandwidth is more than enough unless you become accustomed to enormous amounts of UHD (i.e. 4k) streaming nonstop. With the priority upgrade, we have experienced fewer interruptions with remote realtime communications – VPN, remote desktop, and Microsoft Teams calls (voice and video) are all more reliable and drop less frequently. We do still have minimal obstruction problems that need to be resolved, and I expect that once we verify we’ve eliminated all obstructions, our remaining intermittent connectivity issues will be resolved for good.

The upgraded hardware will also improve service reliability, as it’s able to better maintain a connection through geographic obstructions. Another local Starlink subscriber spent $2500 on a new, high performance dish, and reported an immediate improvement in speed and reliability, so it’s probably worth the investment if your demands require it. It’s expensive enough that we’re going to try other solutions with our existing hardware first, and if that proves insufficient, we’ll consider getting the more expensive dish.

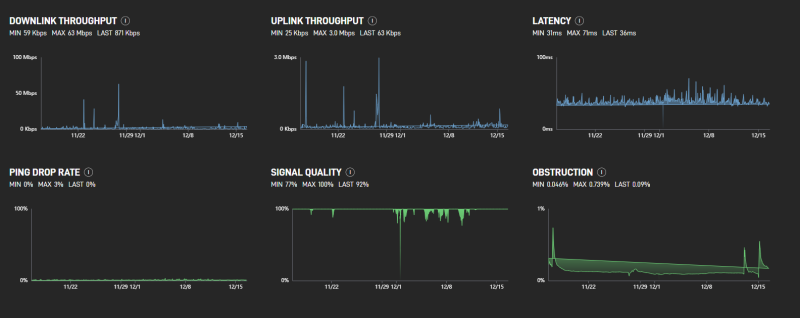

Starlink makes it easy to monitor network performance; the website includes a nice dashboard, which shows up to the last 30 days of performance.

As you can see, our connection is nowhere as fast as, say, Comcast or Google Fiber, but the real use case for Starlink isn’t for people who can easily access superior terrestrial networks; it’s for people who can only access the Internet through some form of radio communications. When your options are traditional geostationary satellite Internet or Starlink, there is no debate: Starlink is infinitely superior to traditional satellite Internet providers. If you’re still limping along with slow, throttled, unreliable rural Internet, it’s definitely worth giving Starlink a look. It is expensive, but it offers functionality that’s just impossible with traditional providers. While HughesNet seems to be doing something interesting in the arena of low-orbit satellite mesh networks, as of now, the company has no offerings using the infrastructure they purchased in December 2022. So until they start competing directly with Starlink’s service, Starlink is without question the best rural Internet option available. We’ve helped a number of people in our local community switch to Starlink, and they’ve all been truly thrilled – especially those who can now video chat with their grandkids!

If you’re mostly reading this review to figure out if Starlink is right for you, I hope I’ve shed some light on its performance, and whether or not it can support full-time remote office work, where realtime communications is a critical requirement. That being said, there’s a whole different aspect to Starlink that I think has gone mostly unnoticed by online journalists and tech pundits.

The potential for…revolution?!

I already briefly detailed how Starlink revolutionizes the technologies used for two-way satellite communications, enabling a network that was previously simply impossible to deploy and support. There is much more to the Starlink picture though: it can bypass essentially the entire current infrastructure of the worldwide commodity Internet – that is, the interconnected global network that you and I use for online communications of all kinds. In space, Starlink’s network uses speed-of-light connectivity (using lasers) to transmit data between satellites, making it possible to quickly connect to other Starlink users without going through the commodity Internet. This excellent article (archive) discusses the subject of Starlink’s satellite intranet, and the potential uses for such a high-speed network, but I find a much more compelling reason to pursue this concept: freedom.

Regardless of one’s personal viewpoints on any of the major geopolitical issues of our time, it goes without saying that Internet censorship and surveillance have become extremely important issues for many millions of people worldwide. Previous whistleblowers in the United States have revealed mass surveillance and data collection on a scale most people didn’t realize was technologically possible, putting a spotlight on the risks presented by a highly centralized Internet architecture.

The Internet runs on a model of implicit trust. There are certain components of the Internet’s fundamental design which rely on the masses – everyone who uses the Internet, everywhere on Earth – maintaining trust in very powerful entities with the ability to exert significant invisible control over the Internet. The domain name system, aka DNS, is built on this model of implicit trust, because DNS requests ultimately fall back on a small list of trusted root DNS providers. You can read more about that here, in an article published by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority. If a particular bad actor wished to make it functionally impossible for anyone, anywhere to access a particular website hosting a particular bit of undesirable information, invading this trust system is a great way of doing so, without most people (or anyone) noticing.

Some of this is essentially unavoidable: DNS is a necessary means of identifying a remote endpoint you want to talk to for some reason. IP addresses are unwieldy (and unreliable, since a great deal of networking involves network address translation and dynamic IP addresses), and we’re running out of them. IPv6 addresses are unusably long as human-readable identifiers, so at some point in large-scale computer networking, something like DNS is pretty much mandatory.

Similarly, the trust model for SSL is centralized, because it’s not very reasonable to expect end users to maintain a list of every single certificate issuer and website they should trust. Instead, major public certificate authorities, like DigiCert and VeriSign, manage the validation of websites, so your devices and browsers automatically trust anything trusted by these root authorities. The trouble is, when a publicly trusted certificate authority is compromised, every single certificate issued by that authority is immediately invalid and untrustworthy, so we as end users have to put a lot of faith in this highly centralized trust model.

So what if there were a decentralized alternative to the current Internet we all know and love? Reimagining the entire Internet is no small feat, and to date, there have been no forces driving the need to decentralize the Internet’s most critical systems and services, so we remain in a sort of stasis, iterating on existing technologies and infrastructure. Much of this is an inevitable side effect of telecommunications companies wanting to maintain the physical networks in which they’ve cumulatively invested billions of dollars, but some of it is simply because there’s no good justification to spend research dollars figuring out novel ways of doing things differently.

Starlink opens entirely new opportunities in this sphere, to rework from the ground up how the Internet functions, and how we can reliably and safely connect to others all over the world without having to constantly worry about centralized managers of access to knowledge and information becoming infiltrated, hacked, corrupted, subverted, or anything else you can imagine might be appealing to an entity looking to, say, overthrow a government…or provide cover for some sort of atrocity committed by a government.

Starlink’s own point-to-point satellite network doesn’t have to rely on any of the common protocols and technologies we use to do things online. There are numerous new possibilities afforded by not having to constantly ensure compatibility with existing technologies. Fortunately, Starlink is economically motivated to make its satellite mesh as efficient, fast, and responsive as possible, and Starlink’s engineers may just develop entirely new technologies we have yet to even imagine.

As the world is rapidly changing around us and we watch history being made in realtime, another oft-ignored aspect of Starlink’s network is deceptively simple: it’s in orbit. No government on Earth can exert authority over what’s in orbit around the planet. There are international treaties in place to ensure communications satellites orbiting Earth are left alone by other sovereign governments (more here), because it’s pretty much impossible for a terrestrial nation or government to claim sovereign rights over a portion of what constitutes “orbiting around Earth.” Even geostationary satellites have to orbit multiple times around the planet in the process of finding and establishing a stationary position in high orbit. So what does this mean in practice? It means a government can’t very successfully prevent its people from connecting to a network to access prohibited, banned, or censored information when that network is in orbit, rather than on the planet’s surface. A government can exert significant control over networks physically within the borders of its jurisdiction, but when it comes to satellite, all a government can do is ban the receiving hardware. The signal itself is present, even if the government says it’s not supposed to be.

Starlink is in a unique position, in my opinion. It has tremendous potential to revolutionize far more than how easy it is to get to the Internet from the remotest reaches of Earth. Only time will tell what Starlink does (or doesn’t do) with this potential.

Gadgeteer Comment Policy - Please read before commenting

Wow! This is a great article, @Claire! Thanks for the details and the nice links for further rabbit holes!