ARTICLE – Instant cameras freeze moments, but this one records them, converts the footage into a scannable code, and prints both on film. The Fujifilm instax mini Evo Cinema captures up to 15 seconds of video, lets you pick a single frame, then embeds a QR link on the print that plays the clip when scanned. It’s a hybrid format that doesn’t quite fit the instant camera category anymore. The misfit quality might be the point if you look at how people actually use instant cameras today. You’re getting both the tangible print and the video context that led to that frozen frame.

Price: $409.95

Where to Buy: Instax US

Video stored on Fujifilm’s servers stays accessible for two years after upload, which sounds generous until you realize what it means: these prints have an expiration date. Scan the code and the video plays with the instax frame overlay intact, keeping the analog aesthetic even in digital playback. After two years, though, the QR code stops working unless you manually re-upload the file. You’re not buying permanent ownership of the video component. You’re renting access to it, and that changes what these prints actually are. Press and hold the shutter to record, release to pause, then review frames on the rear LCD before committing to a print. The tactile print lever mimics older film advance mechanisms even though it serves no mechanical function here. Fujifilm clearly wants this to feel analog despite the server-dependent storage model underpinning the whole system.

Instant film costs money per shot, so the pressure to get it right before printing matters more than it does with phone cameras where you can take fifty versions of the same moment and delete the failures without consequence. The pause-and-review workflow here acknowledges that tension between spontaneity and cost. You’re committing to a specific frame with real consequences. Each print represents a choice you can’t undo. That deliberateness changes how you approach the moment.

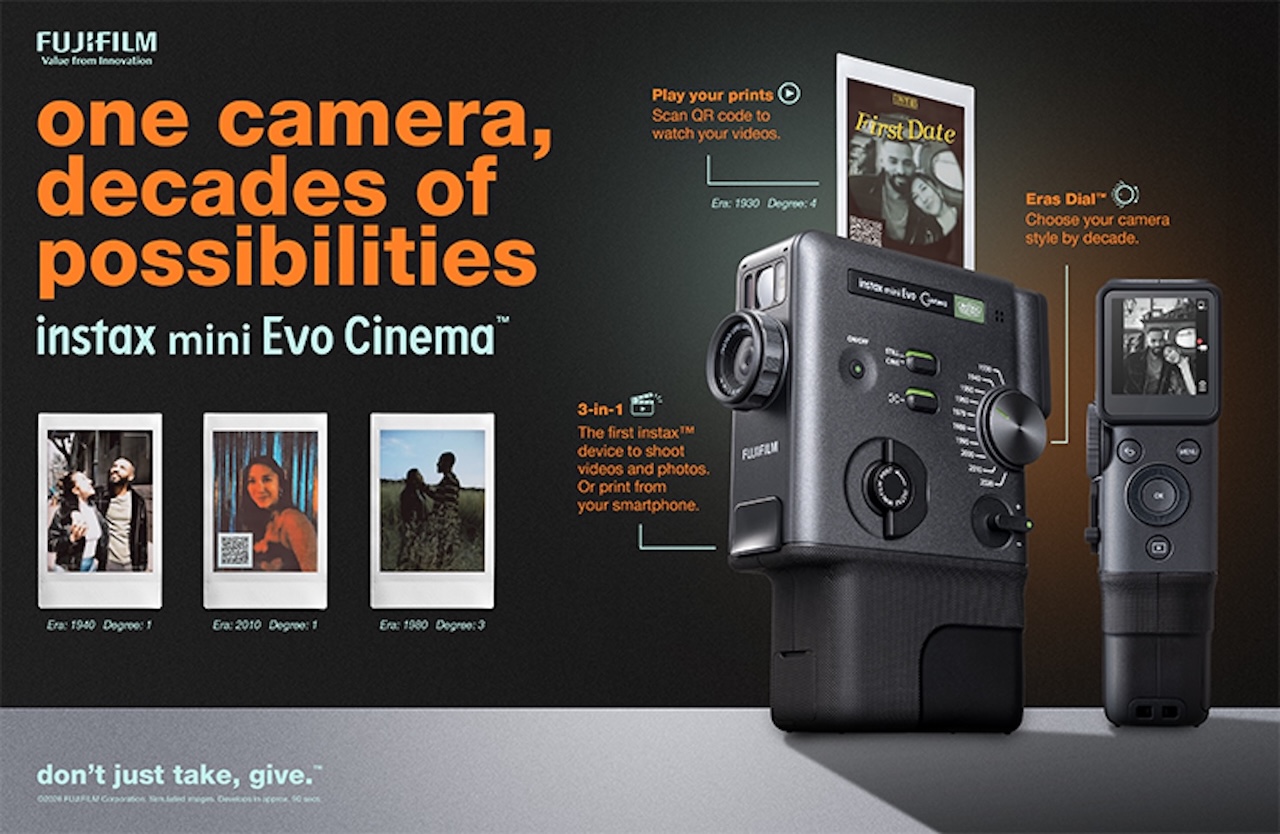

Eras Dial Applies Decade-Specific Film Degradation

Fujifilm’s standout hardware feature is the Eras Dial, which cycles through ten film and video era presets, each with ten adjustable intensity levels for 100 possible effect combinations. “1960” mode mimics 8mm film grain with color shift and subtle frame jitter that replicates the inconsistency of older mechanical formats, capturing the specific texture of home movies from that decade. “1970” recreates the saturated, slightly unstable look of CRT color television broadcasts, complete with edges that bleed and warp in ways that feel organic rather than algorithmic.

“1980” pulls from 35mm color negative stock: softer contrast, warmer midtones, and the kind of faded saturation you see in old family photos stored in basements for decades. Fujifilm didn’t just layer a filter over the image. They added period-appropriate audio artifacts too. The 8mm mode includes mechanical whir and film reel flutter during recording, subtle enough that you notice it immediately if you’re paying attention. The attention to sound design separates this from phone app filters that only touch the visual layer and call it vintage.

Degree control adjusts effect intensity from barely noticeable to aggressively textured, giving you actual control over how vintage you want the footage to look. Set it to 2 or 3 and you get light warmth and grain without visible artifacts dominating the frame, the kind of subtle patina that adds mood without calling attention to itself. Crank it to 10 and you get heavy distortion, color shifts, and noticeable degradation that announces itself before the video even plays, turning your clip into something that looks like it was recorded decades ago and stored poorly. That range matters because not every moment needs to look like it survived a flood, but some moments benefit from looking exactly that way.

Each turn of the dial clicks with tactile feedback, reinforcing the analog interaction Fujifilm designed around. You’re rotating through eras, not scrolling through a dropdown menu, and that physical sensation makes the selection feel more intentional than tapping a screen icon ever could. The click has resistance, requiring deliberate movement rather than accidental swipes. That friction matters when you’re selecting an effect mid-shoot, preventing unintended changes while still allowing quick adjustments.

Certain effects layer in visual noise that changes frame to frame, mimicking the inconsistency of analog playback where no two frames look identical. The “1970” CRT mode adds horizontal scan lines that shift slightly with each second of recording, replicating the instability of cathode ray tube displays in a way that’s convincing enough to fool anyone who didn’t grow up watching VHS tapes.

Vertical Grip Borrows From Fujifilm’s 8mm Heritage

Form factor takes direct cues from the FUJICA Single-8, an 8mm movie camera Fujifilm released in 1965. Vertical grip orientation is designed for one-handed shooting while looking at the rear LCD, though Fujifilm includes a detachable viewfinder accessory if you want that direct sightline instead of staring at a screen. The design choice isn’t just aesthetic nostalgia. Vertical orientation better suits the kind of casual, handheld shooting the camera encourages, feeling more natural for quick capture than traditional horizontal camera grips. The Single-8 reference signals intent: this is meant for spontaneous documentation, not tripod-mounted production work.

Grip attachment improves stability during longer clips, which matters once you pass the 10-second mark and start feeling the weight of holding a vertical form factor steady without support. Without it, the camera feels lighter but less secure, especially if you’re trying to hold steady while recording someone moving or talking, and your hand starts to fatigue faster than it would with a traditional horizontal grip. Accessories come included rather than sold separately, which suggests Fujifilm expects users to customize based on shooting style rather than committing to one fixed configuration. The fact that they don’t charge extra for these components signals that modularity is part of the core product design, not an afterthought. That’s a welcome approach, since many camera makers would sell the grip and viewfinder as premium add-ons.

App Combines Clips and Handles Smartphone Printing

Instax mini Evo app connects via Bluetooth or Wi-Fi, and Wi-Fi is noticeably faster for transferring video files and previewing clips before sending them to the camera for printing, so if you’re working with multiple takes or longer footage, the connection method matters. Speed difference is noticeable enough that you’ll default to Wi-Fi after the first transfer.

App lets you stitch multiple clips into a single video up to 30 seconds long, with opening and ending templates that frame your footage like a home movie project from an era when people edited camcorder tapes into VHS compilations. Poster template feature lets you design prints with titles and text overlays, treating the instax print like a miniature movie poster. Useful for event documentation or storytelling projects where context beyond just the image adds meaning.

App interface isn’t cluttered, but it’s not intuitive either, falling into that awkward middle ground where nothing is obviously broken but nothing feels effortless. Finding the stitching feature takes a few extra taps, and the layout doesn’t follow the same visual logic as most photo apps, so you spend the first session hunting for basic functions. Once you figure out where everything lives, though, the workflow is fast enough that it doesn’t slow down shooting. Learning curve is steeper than it needs to be, but it’s not insurmountable, and after a few sessions the interface becomes familiar enough that you stop thinking about it. The disconnect between the camera’s thoughtful physical design and the app’s less polished navigation is noticeable, like two teams designed them separately without much coordination.

Video Prints Solve the Problem Instant Cameras Created

Instant cameras give you tangible moments, but they lock those moments in stasis, frozen at a single point in time that can’t capture movement, sound, or the way someone’s expression shifts mid-laugh. Video solves that, but video usually stays trapped on your phone or buried in cloud storage where nobody looks at it again because scrolling through hundreds of clips to find one specific moment is exhausting. QR code approach here splits the difference in a way that feels more practical than gimmicky.

You hand someone a physical print, which feels more deliberate and intentional than texting a link or AirDropping a file. They scan it and the video plays with the instax frame embedded around it, preserving the instant camera aesthetic even in digital playback. Shareable without requiring the recipient to download an app, create an account, or navigate through any friction that would make them give up halfway through. The QR code is standard, so any camera app can read it without specialized software. Immediacy matters when you’re trying to share something in the moment, and the print works as both a physical keepsake and a digital trigger without requiring the recipient to make choices about how to receive it.

Two-year server storage window is generous compared to most free cloud services, but it’s not permanent, and permanence is what people expect from physical prints. After two years, the QR code stops working unless you manually re-upload the file, which means these prints exist in a strange liminal space between analog and digital where neither format fully commits to its strengths. You’re renting the video component, not owning it outright, and that fundamentally changes the artifact you’re holding.

Fujifilm could have stored video locally on the camera with expandable storage, eliminating server dependency entirely, or offered unlimited cloud hosting with permanent access instead of the two-year window. Both options would have complicated the product and inflated the price beyond what most casual users would tolerate, and both introduce new failure modes that would require customer support infrastructure Fujifilm probably doesn’t want to manage.

QR code embeds directly on the print during the printing process, not as a separate sticker or attachment, which keeps the design clean and integrated. Integration is seamless, but it also means you can’t update the linked video later without printing a new photo. If you want to swap out the clip or edit the footage, you’re out of luck unless you waste another sheet of film. Intentional design choice: Fujifilm wants each print to be a fixed artifact, not a dynamic link that changes over time. That permanence aligns with traditional photography philosophy, where what you capture is what you keep. The downside is you lose the flexibility that digital formats typically offer, where you can refine and improve content after the fact. Static by design, which cuts both ways depending on how you value permanence versus iteration.

Server dependency means these prints don’t work offline, which is a meaningful limitation for a format marketed as tangible and physical rather than cloud-based and ephemeral. Scan the code without internet access and nothing happens. Print becomes a still photo again until connectivity returns. If you’re handing someone a print at a location with spotty signal or no Wi-Fi, the video layer disappears entirely, and you’re left explaining why the QR code isn’t working instead of sharing the moment you captured.

Who This Is For

Works best for people who already use instant cameras but want more flexibility than a static photo offers without fully committing to digital-only formats. Event documentation, travel storytelling, and family memories all benefit from the video layer while keeping the print format that makes sharing feel more intentional than sending files. If you like handing people physical objects instead of links, this makes sense. The hybrid approach works if you value both tangible prints and the narrative depth video provides. It’s less appealing if you prefer one format over the other exclusively.

If you specifically print photos to avoid digital clutter and server dependency, QR code setup might feel like a compromise that undermines the whole point of shooting on film. You’re back to depending on internet access, cloud storage, and app compatibility to make the print work as intended, which reintroduces all the friction instant cameras were supposed to eliminate.

Price: $409.95

Where to Buy: Instax US

The camera launched in Japan on January 30, 2026 and is now available in the U.S. Given the feature set and included accessories, pricing sits at the higher end of Fujifilm’s instant camera lineup. The video functionality, era effects system, and included grip and viewfinder accessories place this above entry-level instant cameras in both capability and cost. Pricing reflects the hybrid nature of the device, positioned as a premium option for users who want more than basic instant printing.