CES 2026 NEWS – Most accessibility technology settles for workarounds. It finds clever ways to route around limitations rather than confronting them directly. The white cane extends reach by a few feet. Screen readers translate visual interfaces into audio. Smartphone apps identify objects when you point your camera at them. Each solution adds capability, but the fundamental relationship between a blind person and their environment stays the same: reactive, dependent on external input, constrained by what the tool can detect in a narrow window.

The real question is whether navigation technology can move from assistance to genuine spatial awareness.

.Lumen thinks the answer requires borrowing from an entirely different industry. The Romanian company spent five years developing a headset that processes the world the way a self-driving car does, then translates that information into something a human can feel and hear without seeing anything at all.

Add The Gadgeteer as a preferred source to see more of our coverage on Google.

Why This Exists

Guide dogs remain the gold standard for independent navigation. A well-trained dog anticipates obstacles, reads traffic patterns, and adapts to changing environments in ways that no previous technology could match. But guide dogs come with significant constraints. Waiting lists stretch for months or years. Training requires intensive commitment from both dog and handler. The ongoing responsibility of caring for a living animal adds complexity to daily life. And when a guide dog retires after eight to ten years of service, the cycle starts over.

.Lumen founder Cornel Amariei grew up around family members with disabilities in Romania. He watched the gap between what technology could theoretically accomplish and what actually reached people who needed it. By 2020, autonomous vehicle sensors had become sophisticated enough to map environments in real time with remarkable accuracy. The processing power to interpret that data had shrunk to portable sizes. What hadn’t happened was anyone packaging those capabilities into something a blind person could wear.

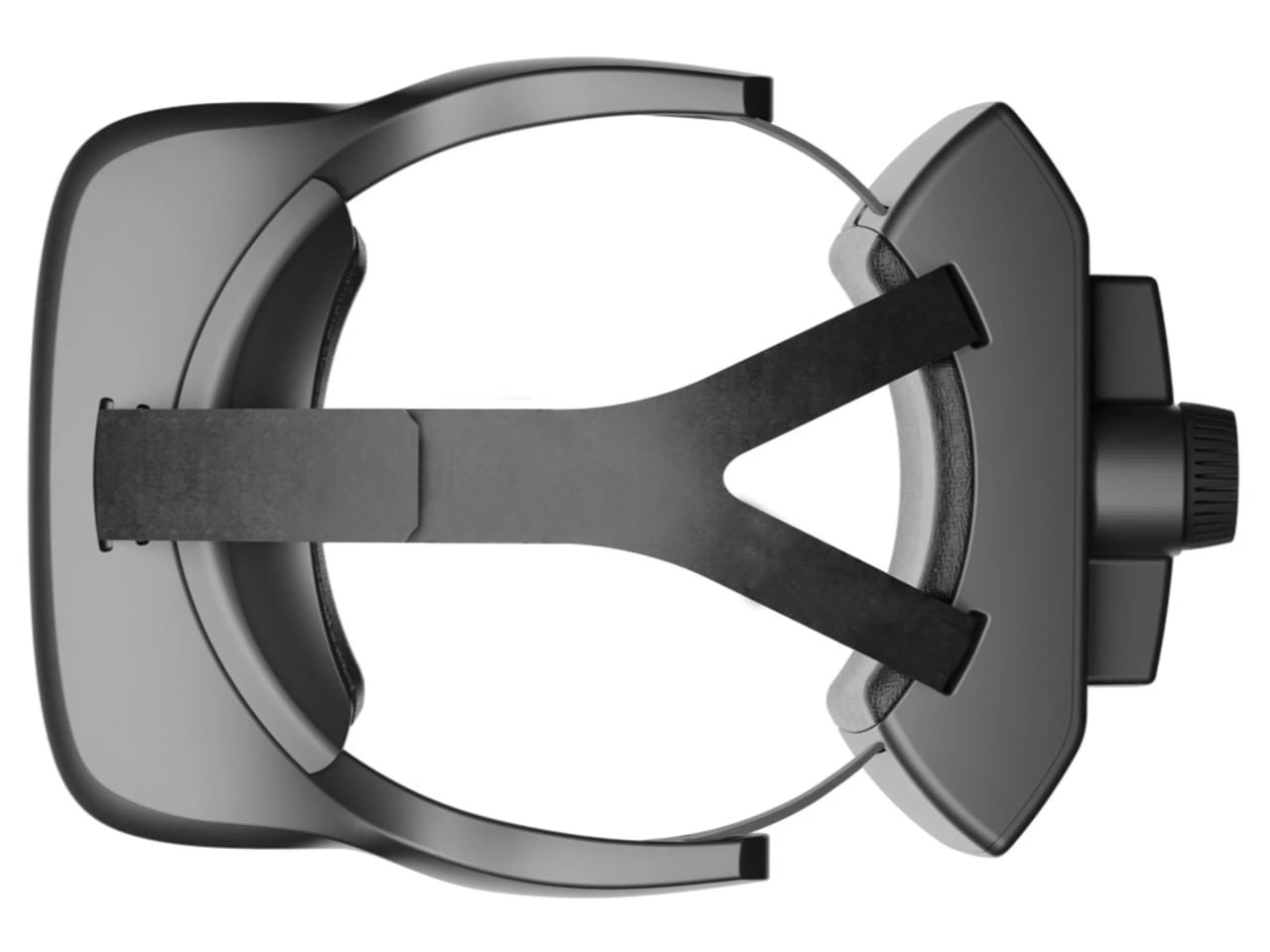

The headset that emerged looks nothing like glasses. It resembles a VR headset with a prominent sensor array mounted on the forehead and a battery pack balanced at the rear. The form factor prioritizes function over aesthetics, which makes sense given that the wearer isn’t looking at it.

The Sensing Architecture

Six cameras capture the environment from multiple angles. Two infrared laser projectors enable operation after dark, when visible light cameras would struggle. Three inertial measurement units track head position and movement with the kind of precision usually reserved for aerospace applications. GPS provides macro-level positioning while the cameras handle micro-level obstacle detection.

The result is a sensing envelope that extends well beyond what a white cane can reach. The system flags overhead obstacles that would clip someone’s head before contact. Ground-level hazards like puddles, ice patches, and uneven pavement register early enough to adjust stride. Stairs announce themselves from several feet away rather than when a foot finds empty air.

.Lumen claims the system achieves roughly 70% of a self-driving car’s sensing performance using hardware one-tenth the size. That’s an interesting benchmark because it acknowledges the gap while framing it as acceptable for pedestrian speeds. You don’t need automotive-grade precision when you’re walking rather than driving.

How It Communicates

The headset translates spatial data into two output channels. Haptic feedback through the forehead delivers directional information via precise vibration patterns. The sensation guides movement without requiring conscious interpretation, similar to how a hand on your shoulder can steer you through a crowd. Beamforming speakers provide audio cues and voice feedback without blocking environmental sounds.

AI processes sensor data more than 100 times per second, which is fast enough that the guidance feels continuous rather than choppy. Road segmentation algorithms identify crosswalks, curbs, and lane markings. The system recognizes doors, bus stops, and building entrances.

Voice commands enable destination-based navigation. You can ask for directions to preset locations like home or work, or request guidance to nearby businesses. .Lumen says they’re developing more natural language processing that would understand requests like “take me to my office” and provide turn-by-turn guidance all the way to your desk.

The Weight Question

At 2.2 pounds, the headset weighs about the same as a half-face motorcycle helmet. That’s noticeable. Battery life runs approximately two hours, which covers most urban excursions but wouldn’t last through a full day of travel. The form factor trades portability for capability.

These constraints reflect where the technology currently sits. Sensor packages that can map environments in real time consume significant power. Processing that data locally rather than relying on cloud connectivity requires onboard computing. The engineering challenge involves cramming autonomous vehicle capabilities into something that sits on a human head, and current battery and miniaturization technology imposes hard limits.

Future iterations will presumably shrink as components improve. But the current version prioritizes proving the concept works over achieving consumer-friendly dimensions.

Testing and Validation

.Lumen reports more than 400 blind users have tested the headset across 40+ countries in real urban and rural environments. The company secured CE certification, which clears the path for European sales. Pre-orders hit 1,500 units within ten days of opening, suggesting genuine demand from the blind community.

CES 2026 will provide the first major public demonstration. A subsequent demo tour across Romanian cities will give potential users hands-on experience before the European launch in early 2026.

The Price Reality

At €9,999 (approximately $11,800 USD), the .Lumen headset represents a significant financial barrier, though what it offers isn’t easily measured in dollars. That price point reflects low-volume manufacturing of specialized hardware rather than consumer electronics economics. Insurance coverage, accessibility grants, and assistive technology funding programs may offset costs for some users, but the financial barrier remains significant.

For context, a trained guide dog costs between $20,000 and $50,000 when you factor in breeding, training, and placement expenses. Most guide dog organizations provide dogs at no cost to recipients, absorbing those expenses through donations. .Lumen doesn’t have equivalent charitable infrastructure, so the full price falls to buyers or their insurance.

Who Should Skip This

The .Lumen headset isn’t for everyone in the blind community. If you’ve established effective navigation strategies with existing tools and don’t feel limited by their constraints, a five-figure investment in unproven technology may not make sense. If you’re uncomfortable with conspicuous wearable devices, the current form factor offers no subtlety. If you need all-day battery life for work or travel, two hours won’t suffice.

People with partial vision might find the headset redundant depending on what their remaining sight can accomplish. Those who already work successfully with guide dogs may see limited benefit from switching to an electronic alternative, especially given the established bond and proven reliability of a trained animal.

The ideal early adopter is someone whose current navigation options feel genuinely limiting, who has access to funding or coverage, and who’s comfortable being an early user of technology that will evolve significantly over coming years.

What This Signals

The .Lumen headset matters beyond its immediate functionality because it demonstrates that autonomous vehicle sensing technology can transfer to accessibility applications. The same AI that helps cars avoid pedestrians can help blind pedestrians navigate around obstacles. The same sensors that map roads can map sidewalks, interiors, and unfamiliar environments.

If the concept proves viable at scale, competition and iteration will eventually drive down costs and improve form factors. We’ve covered enough assistive technology launches to know that first-generation devices rarely represent the final form. What they do represent is proof that the underlying approach works well enough to build on.

.Lumen isn’t claiming to have solved blindness navigation. They’re claiming to have found a technical architecture that could eventually approach the spatial awareness we take for granted. Whether they’re right depends on real-world performance that no amount of controlled testing can fully predict.

The CES demos will provide the first broad look at what five years of development produced. After that, the blind community will have its own verdict.

📡 CES 2026 Coverage

Want more from the show floor?

We’re covering the biggest announcements, wildest concepts, and gear that actually matters from CES 2026.